The train rattled into Vienna’s Hauptbahnhof on a crisp February morning in 2022, its brakes screeching as it disgorged a flood of weary Ukrainian refugees. Mothers clutched children, their faces etched with exhaustion and fear, fleeing the thunder of Russia’s invasion. Aid workers swarmed the platforms, offering blankets, hot tea, and a flicker of hope. Vienna, a city of imperial charm and quiet wealth, became one of the first sanctuaries for those escaping the war.

The Golden Quarter

But not all arrived on foot or by rail. Beyond the crowded station, a different scene unfolded: sleek luxury cars with Ukrainian plates rolled into the city—Mercedes G60s, Range Rovers, BMW SUVs—gleaming symbols of a starkly different exodus.

At first, the Viennese embraced the newcomers with open arms. The city council, in a gesture of solidarity, waived parking fees for Ukrainian vehicles, a policy met with nods of approval from locals. Refugees needed support, after all, and Vienna had a long history of hospitality. But as spring turned to summer, the mood shifted. The free parking spaces weren’t scattered across humble suburbs; they clustered in the heart of the city—around the opulent Golden Quarter, near the “Am Hof” garage by the Hyatt Hotel, in districts where rent rivaled Paris. And the cars weren’t modest sedans.

The Golden Car

A golden Audi A8, its paint shimmering like liquid wealth, sat parked at “Am Hof,” its Ukrainian plates a quiet boast. Two young women, draped in designer coats, stepped out, laughing as they vanished into the boutiques of Louis Vuitton and Chanel. Locals began to mutter. How could war-torn Ukraine, a nation pleading for aid, produce such ostentatious escapees?

The luxury cars became a fixture, a rolling paradox against Vienna’s cobblestone streets. A black Range Rover idled outside a Michelin-starred restaurant; a Mercedes S-Class gleamed in the evening light near St. Stephen’s Cathedral. The Viennese, once sympathetic, grew irritated. “Economic refugees,” they grumbled, noting the young men behind the wheels—men who seemed too polished, too carefree, for a country in chaos. By late 2022, the city scrapped the free parking perk, but the cars remained, their presence a stubborn riddle. At “Am Hof,” where the elite once parked their Porsches, Ukrainian plates now dominated. The golden A8 returned often, a silent taunt to those who wondered: Where did the money come from?

The answer, whispered in Vienna’s insider circles, was as old as the city’s shadowy past. Ukraine, long branded Europe’s corruption capital, had been bleeding wealth for decades. In 2013, Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index gave Ukraine a dismal 25 out of 100, ranking it 144th of 177 nations—a score unchanged from years of oligarchic plunder. By 2016, it matched Russia’s graft-ridden reputation, with 38% of Ukrainians admitting to paying bribes for basic services in 2017, per Transparency International data. The war only accelerated the flow. Billions in aid poured into Ukraine, but so did opportunities for skimming—weapons deals, reconstruction funds, black market trades. And Vienna, with its discreet banks and historic role as a laundering hub, was a natural destination.

The Money Laundering Legacy

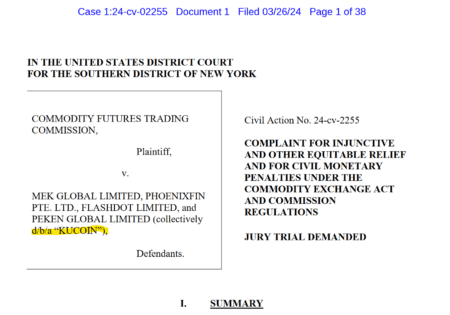

During the Iron Curtain era, Vienna thrived as a conduit for Soviet cash, its neutrality a cloak for illicit transfers. A 2015 CIA report, buried in declassified archives, detailed how Ukrainian oligarchs and businessmen funneled fortunes through Viennese institutions, leveraging lawyers whose offices doubled as cash depots. Raiffeisen Bank, a fixture in Central Europe, faced scrutiny for handling suspect funds—Reuters reported in 2023 that its Austrian branches processed millions linked to Eastern European corruption. The city’s legal elite, some named in hushed tones over schnitzel and wine, greased the wheels, their Rolodexes thick with Ukrainian contacts. Post-invasion, this pipeline didn’t dry up; it widened.

Take Oleksandr, a fictional composite of this new Viennese elite. At 29, he arrived in 2022, his family in tow, driving a matte-black BMW X7. Back in Kyiv, he’d owned a logistics firm—on paper, a modest operation. In truth, it was a front, shuttling cash from wartime contracts: overpriced fuel for the military, ghost shipments of medical supplies. Millions flowed into Cyprus shell companies, then trickled into Vienna’s banks, cleansed by a lawyer known for “creative accounting.” Oleksandr’s wife, Iryna, adorned in Gucci, sipped espresso at Demel, while their teenage son test-drove a Porsche at a dealership near the Ringstrasse. Their wealth wasn’t questioned; it was admired, envied, and quietly resented.

The Golden Quarter, once a playground for Russian oligarchs until sanctions exiled them, now buzzed with Ukrainian accents. Cartier bags swung from arms, Tod’s loafers clicked on marble floors. The “Am Hof” garage, steps away, housed their chariots—symbols of a war’s dark underbelly. Posts on X from early 2025, like those from @FinTelegram, noted the trend: “Luxury cars in Vienna’s priciest garages, full of young Ukrainians. Only the poor fight, it seems.” Another quipped, “Ukrainian money washes clean in Vienna—always has.” The sentiment echoed a gritty truth: while Ukraine’s soldiers bled, its profiteers prospered abroad.

Yet the story gnawed at Vienna’s conscience. Were these refugees victims of circumstance or architects of exploitation? The luxury cars, parked brazenly in the city’s heart, offered no answers—just a glittering challenge to look deeper. For every Oleksandr, countless others languished in Ukraine, their lives upended by the same war that enriched a few. In Vienna, the golden A8 rolled on, a mute witness to a tale as old as greed itself, refracted through the prism of a modern tragedy.

Share Information

Do you have information about Russian money in Vienna or money laundering via Vienna? Then please share this information with us via our whistleblowing system, Whistle42.